In Part 1 of this series, the spectrum efficiency and advantages of using MPEG-4 compression for DTV transmission were explored in the context of the transition to ATSC 3.0 broadcasting.

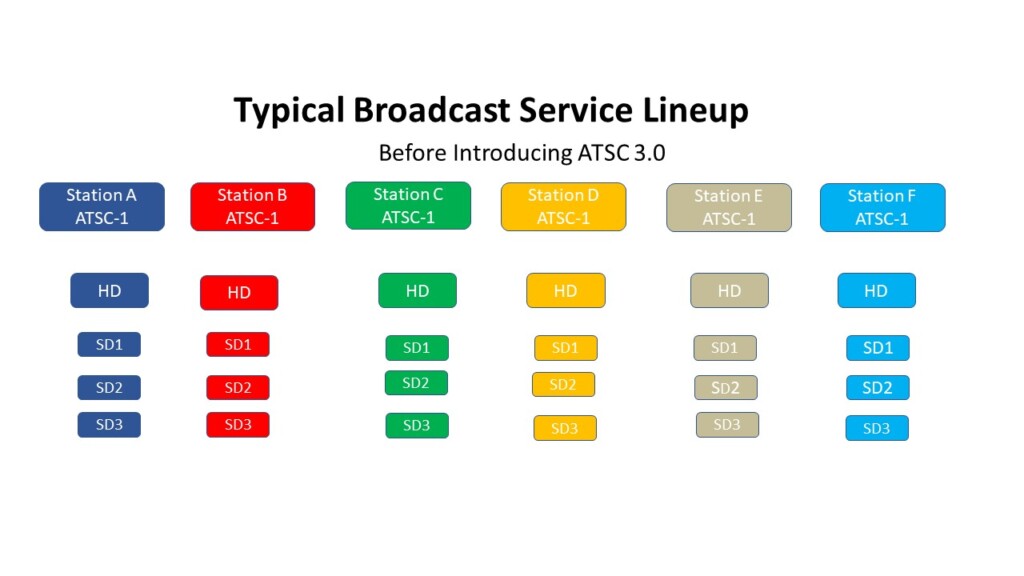

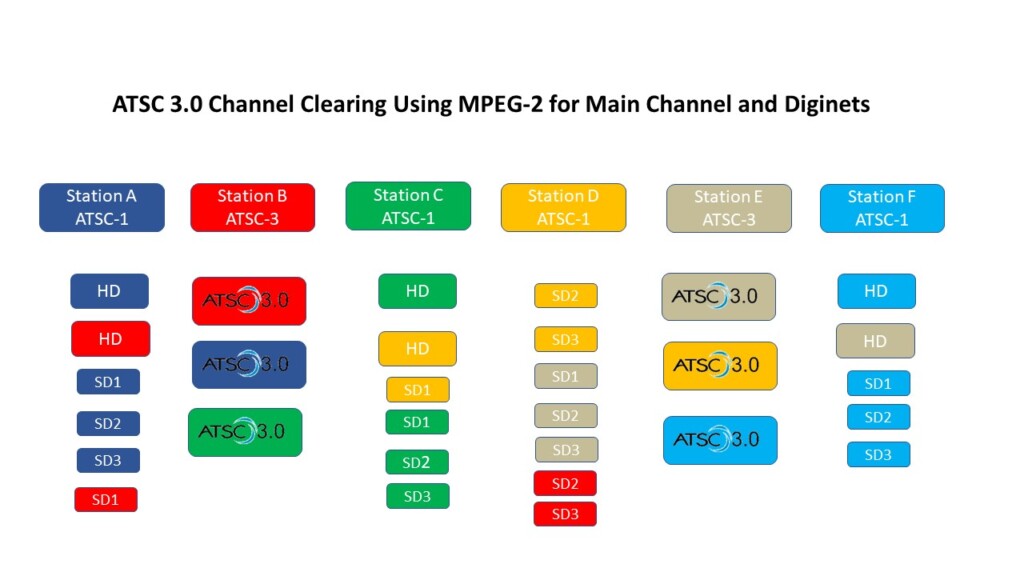

Using the guidelines from Part 1 for a theoretical example, consider a market with six TV stations, each with one HD signal (the primary signal) and three SD signals (subchannels or so-called diginets) in their multiplex. Moving some of these services from one channel to another results in a maximum of two RF channels being freed up for ATSC 3.0, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 below.

Figure 1: A theoretical TV market with 6 television stations, each with one HD and three SD program streams.

Figure 2: Example of using channel sharing to free up the maximum number of channels for ATSC 3.0 in a theoretical market with six stations, each with one HD and three SD streams.

Given the huge efficiency benefits of ATSC 3.0 compared to ATSC-1, clearing two RF channels for ATSC 3.0 services that are shared by six stations as shown above is certainly enough to launch the new service, but if it were possible to free up additional RF channels the resulting expanded bandwidth for ATSC 3.0 would allow those new services to be even more compelling. Unfortunately, in this theoretical example, the only way to do that would be to drop some of the services or degrade the quality level of some or all of the program streams by reducing their bit rates, neither of which is a desirable action from a business viewpoint.

Given the huge efficiency benefits of ATSC 3.0 compared to ATSC-1, clearing two RF channels for ATSC 3.0 services that are shared by six stations as shown above is certainly enough to launch the new service, but if it were possible to free up additional RF channels the resulting expanded bandwidth for ATSC 3.0 would allow those new services to be even more compelling. Unfortunately, in this theoretical example, the only way to do that would be to drop some of the services or degrade the quality level of some or all of the program streams by reducing their bit rates, neither of which is a desirable action from a business viewpoint.

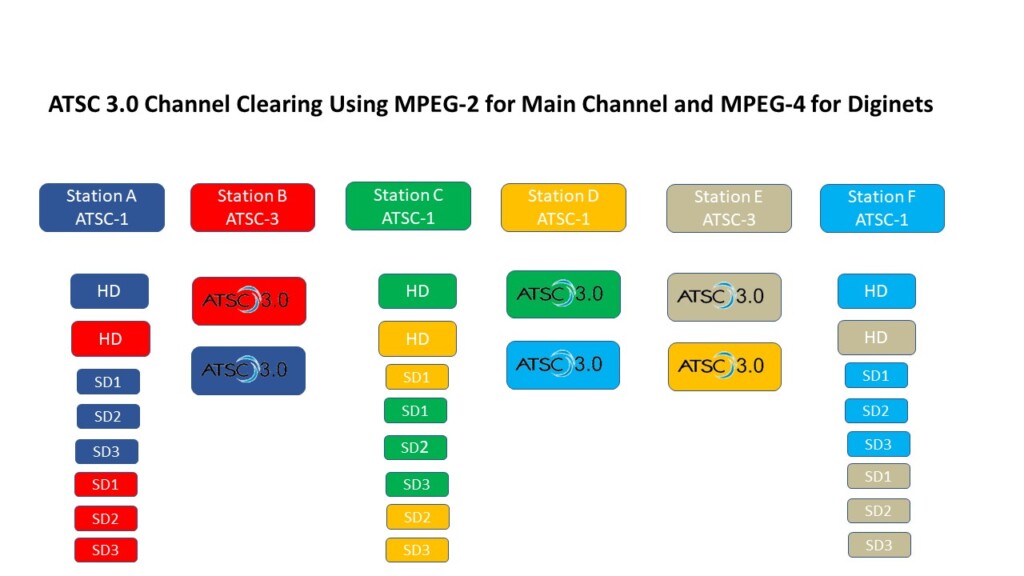

With this in mind, converting current MPEG-2-encoded multicasts/diginets to MPEG-4 encoding on a wide scale could free up more RF channels in a broadcast market for ATSC 3.0 without discontinuing or degrading existing services. Using the previous theoretical example, switching compression for diginets to MPEG-4, and assuming MPEG-4 encoding is twice as efficient as MPEG-2, would allow a third RF channel to be freed up for ATSC 3.0, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Using MPEG-4 compression for multicasts/diginets, a third RF channel can be freed up for ATSC 3.0 in the theoretical TV market shown in Figure 1.

Thus, with MPEG-4 encoding for all diginets, half of the six RF channels in the market could be used for ATSC 3.0. And since the HEVC compression scheme used in ATSC 3.0 is roughly four times the efficiency of MPEG-2, and ATSC 3.0 transmission efficiency in bits/hertz is better than ATSC-1, the result is that, even with two stations sharing one ATSC 3.0 RF channel, more programs could be offered in ATSC 3.0 compared to ATSC-1, or programs with higher video/audio quality, higher robustness level or augmented data broadcast services could be supported.

In the longer-term future, it may become practical to consider switching ATSC-1 primary program compression to MPEG-4. This brings up issues such as to how to protect all legacy viewers from being disenfranchised and would require an FCC rule change. It’s a subject for another day. But if ATSC-1 was switched to MPEG-4 encoding for all programs in the previous theoretical example, four of the six RF channels in the previous theoretical market could be made available for ATSC 3.0 services, increasing the potential yet again for new services using the extra ATSC 3.0 bandwidth.

The third and final part of this blog series will look at some of the current regulatory constraints on channel sharing among stations that are presenting challenges for the transition to ATSC 3.0.