For those immersed in new technology for broadcasting, ATSC 3.0 and Next Generation TV are nothing new, as we’ve been working with the associated technological standards, equipment development and policy issues for over a decade. But as stations begin to actually deploy services and manufacturers launch retail products, Next Gen TV is being introduced to the general consumer population, where ultimately it will thrive or fail in the court of popular opinion, so it’s important to get the introduction right.

The new watchnextgentv.com website, which was soft-launched at the end of October and more formally announced by Pearl TV on November 16, is an important initial foray in reaching out to consumers. Among other information, the website shows the current markets (and stations within those markets) that have Next Gen TV services in place, as well as the upcoming markets that are slated to launch in the coming months. The website provides plain language explanations of some of the features that are expected to be embraced by consumers and a FAQ section has answers to common questions that are likely to get asked. Importantly, watchnextgentv.com also has links to specific TV set models that are Next Gen TV-capable, currently around 20 or so model/size combinations, available from LG, Sony and Samsung. In addition to announcing the watchnextgentv.com website, the November 16 Pearl TV press release also announced two other parts of an overall Next Gen TV promotional campaign that will begin this month: on-air advertising with customized TV spots in target markets and online promotions executed by individual stations to encourage consumers to learn more.

It’s a great start, but only one of the first efforts in what must eventually become a widespread multi-pronged national promotional campaign touting the new service to consumers.

The big indicator for consumers to have confidence that they are buying a Next Gen TV set that will consistently function properly is to look for the NEXTGEN TV logo, publicly announced by the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) in fall 2019. The full set of ATSC 3.0 features and services is a long and complex list. It’s a lot more complicated than just having an RF tuner/decoder that can process video images and audio signals. As such, the industry realized that a logo certification program would be most worthwhile if it was associated with a comprehensive conformance test plan as part of a self-certification process for set manufacturers. The overall logo certification and conformance test program, administered by CTA, has been developed over the past several years with funding and guidance from NAB and CTA with active participation from the ATSC Conformance Implementation Team, as well other industry stakeholders. Due to the timing of the test program development and manufacturer approval and marketing cycles, the NEXTGEN TV logo may not be evident on all TV set products this calendar year. But the program is in full swing for 2021 and subsequent years and the most recent version of approved tests has recently been announced by CTA for 2021 consumer products. The conformance test program currently includes over 135 tests covering 150 unique requirements. That may seem like a lot but it’s really just the beginning.

The big indicator for consumers to have confidence that they are buying a Next Gen TV set that will consistently function properly is to look for the NEXTGEN TV logo, publicly announced by the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) in fall 2019. The full set of ATSC 3.0 features and services is a long and complex list. It’s a lot more complicated than just having an RF tuner/decoder that can process video images and audio signals. As such, the industry realized that a logo certification program would be most worthwhile if it was associated with a comprehensive conformance test plan as part of a self-certification process for set manufacturers. The overall logo certification and conformance test program, administered by CTA, has been developed over the past several years with funding and guidance from NAB and CTA with active participation from the ATSC Conformance Implementation Team, as well other industry stakeholders. Due to the timing of the test program development and manufacturer approval and marketing cycles, the NEXTGEN TV logo may not be evident on all TV set products this calendar year. But the program is in full swing for 2021 and subsequent years and the most recent version of approved tests has recently been announced by CTA for 2021 consumer products. The conformance test program currently includes over 135 tests covering 150 unique requirements. That may seem like a lot but it’s really just the beginning.

For context, in Europe, the HbbTV Association recently celebrated its 10-year anniversary. This group manages the logo program for the hybrid broadcast broadband TV features found in DVB TV products. The first conformance test suite for HbbTV was released in 2012, consisting of 250 tests. With 17 subsequent revisions of the test suite released since that time, the latest test release from summer 2020 has grown to now include a total of 2,759 test cases. The NEXTGEN TV logo certification program may or may not exactly follow the example of HbbTV, but the trend toward increasingly more tests being included in the logo certification program as time passes is likely to hold true with NEXTGEN TV.

For context, in Europe, the HbbTV Association recently celebrated its 10-year anniversary. This group manages the logo program for the hybrid broadcast broadband TV features found in DVB TV products. The first conformance test suite for HbbTV was released in 2012, consisting of 250 tests. With 17 subsequent revisions of the test suite released since that time, the latest test release from summer 2020 has grown to now include a total of 2,759 test cases. The NEXTGEN TV logo certification program may or may not exactly follow the example of HbbTV, but the trend toward increasingly more tests being included in the logo certification program as time passes is likely to hold true with NEXTGEN TV.

![]() As another confirmation of current implementation and deployment trends, the ATSC 2020 NextGen Broadcast Conference, held remotely on October 26 as part of the NAB Show New York virtual event, covered the Next Gen TV rollout plans from both the transmission and reception vantage points. The “NEXTGEN TV is Ready at Retail” session featured executives from LG, Samsung, Sony and Dolby detailing their planned product launches while the “All Systems Go for Deployment” session included representatives from Fox, Nexstar, Sinclair and Edge Networks discussing Next Gen TV market launches.

As another confirmation of current implementation and deployment trends, the ATSC 2020 NextGen Broadcast Conference, held remotely on October 26 as part of the NAB Show New York virtual event, covered the Next Gen TV rollout plans from both the transmission and reception vantage points. The “NEXTGEN TV is Ready at Retail” session featured executives from LG, Samsung, Sony and Dolby detailing their planned product launches while the “All Systems Go for Deployment” session included representatives from Fox, Nexstar, Sinclair and Edge Networks discussing Next Gen TV market launches.

For access to these insightful recorded sessions and others from the ATSC conference, register for a NAB Show NY Marketplace Pass using code RALLY4 for free registration. The ATSC 3.0 Fall 2020 Progress Report released by ATSC during NAB Show New York also provides detailed information on the general state of industry readiness and availability of professional and consumer products.

For access to these insightful recorded sessions and others from the ATSC conference, register for a NAB Show NY Marketplace Pass using code RALLY4 for free registration. The ATSC 3.0 Fall 2020 Progress Report released by ATSC during NAB Show New York also provides detailed information on the general state of industry readiness and availability of professional and consumer products.

It’s still a little early, since we’re just at the beginning of the new service launch, but it will be time in the not-too-distant future to start thinking about the end goal for Next Gen TV; i.e., whether it will always be just an add-on enhancement for the existing DTV service or a full transition. The dictionary defines a transition as “the process or a period of changing from one state or condition to another” (emphasis added). It’s difficult not to desire setting the goal to be a full transition to Next Gen TV since the maximum benefits of Next Gen TV cannot be realized until all broadcast spectrum is available for use for Next Gen TV services. Until that time, a significant amount of spectrum (i.e., some number of 6 MHz TV channels in each market) will be necessary to provide continued DTV service, in parallel with a Next Gen TV service that requires the maximum amount of spectrum available in order to realize its full potential for consumers.

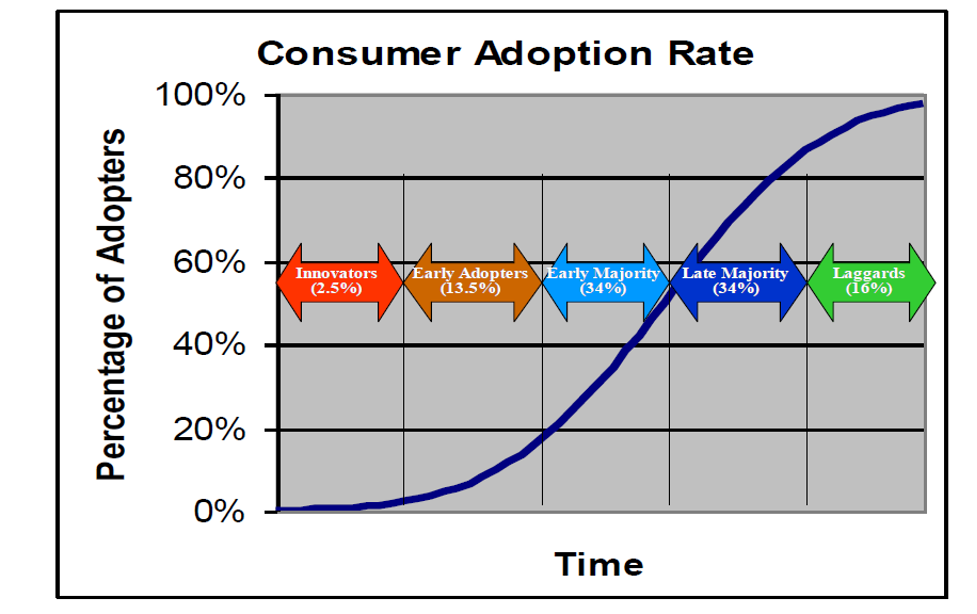

Starting a transition to new TV technology is easier than finishing it, as exemplified in the DTV transition in the U.S. that began in the late 1990s and concluded with the cessation of analog broadcasting in June 2009 following a massive public education effort. A book about the DTV public relations campaign published in late 2018 by former NAB President David Rehr and can be found here. A paper by this blog’s author published in the 2006 NAB Broadcast Engineering Conference Proceedings titled “Completing the DTV Transition: Digital Life After the Death of Analog” discusses the general theoretical model of consumer adoption of new technologies and provides an early 2006 perspective on specifically applying those principles to achieving the completion of the DTV transition. Students of history, those interested in reliving that time or desperate insomniacs can read the full paper here. For everyone else, a few excerpts should be adequate to learn the key points. Figure 1 from the paper is shown below, which illustrates the typical S-shaped adoption pattern of innovations along with the associated adopter categories, followed by some explanatory text about how technology diffusion processes can accelerate (note that the virus analogy in the text seems oddly harmonious with the current times).

Figure 1 from the 2006 NAB Broadcast Engineering Conference Paper “Completing the DTV Transition”

“In the diffusion process, a crucial concept is that of critical mass, the point at which enough adopters of an innovation exist that the further rate of adoption becomes self-sustaining. Prior to reaching critical mass, the rate of adoption is relatively slow; after it is achieved, the rate of adoption accelerates. Critical mass has been observed to often occur between 5% and 20% of total cumulative adoption, the exact point being specific to the innovation under study.

A close cousin to critical mass, in more vernacular terms, is what has been called the “tipping point” for a technology. (See The Tipping Point, by Malcolm Gladwell, Little, Brown and Company, 2002.) The central principle of the “tipping point” theory is that the emergence of popular products, trends and so forth can be best analyzed by thinking of them as epidemics, understanding that their dissemination is similar to the spreading of a virus. Adoption of new products, like the spread of viruses, can take place similarly to that observed in contagion studies in epidemiology, whereby seemingly small changes in contact, or communication patterns can have unexpected large overall effects. And perhaps most importantly, in viral epidemics, and adoption of popular products, overall change can happen suddenly at one dramatic moment, that moment being called the tipping point.”

As the Next Gen TV transition gets underway, hopes abound for quickly developing a critical mass level of adoption and a tipping point for the progression of the transition. However, completing an innovation transition, even one that has progressed rapidly through the first four adopter categories, can get held up by the “laggards.” The characteristics of laggards in innovation transitions are described in the 2006 NAB Broadcast Engineering Conference paper, quoting author Everett M. Rogers from his book Diffusion of Innovations, Fifth Edition, (2003):

“Laggards are the last in a social system to adopt an innovation. They possess almost no opinion leadership.1 Laggards are the most localite2 of all adopter categories in their outlook. Many are near isolates in the social networks of their system. The point of reference for the laggard is the past. Decisions are often made in terms of what has been done previously, and these individuals interact primarily with others who also have relatively traditional values. Laggards tend to be suspicious of innovations and of change agents. Their innovation-decision process is relatively lengthy, with adoption and use lagging far behind awareness-knowledge of a new idea. Resistance to innovations on the part of laggards may be entirely rational from the laggards’ viewpoint, as their resources are limited and they must be certain that a new idea will not fail before they can adopt. The laggard’s precarious economic position forces the individual to be extremely cautious in adopting innovations.

1 Rogers defines opinion leadership as “the degree to which an individual is able to influence other individuals’ attitudes or overt behavior informally in a desired way with relative frequency.”

2 Localite or, at other end, cosmopolite communication channels refer to the degree to which a communication channel links an individual with sources outside that individual’s social system.”

A famous historical example of the laggard issue in broadcast television is the case of the transition from 405 to 625 scanning lines in the United Kingdom, where the unfortunately named “last granny problem” was at least partially responsible for the 20-year-plus 405/625-line simulcast period until 405-line broadcast transmissions were finally discontinued completely in 1985.

A famous historical example of the laggard issue in broadcast television is the case of the transition from 405 to 625 scanning lines in the United Kingdom, where the unfortunately named “last granny problem” was at least partially responsible for the 20-year-plus 405/625-line simulcast period until 405-line broadcast transmissions were finally discontinued completely in 1985.

In the case of the U.S. DTV transition, the conundrum of the laggard category stalling the transition to all-digital television was ultimately solved by government intervention, motivated mainly by the twin desires of providing more spectrum for mobile broadband service and the lure of large sums of money to come from auctioning the broadcast spectrum: phased-in requirements for DTV broadcasts by all broadcasters, phased-in requirements for DTV reception capability in all receivers, labeling and signage requirements for products at retail establishments, cable carriage requirements, on-air notice requirements, a date certain for analog TV shut-off and a discount coupon program run by the federal government to offset the cost of digital-to-analog converter boxes for consumers.

In the case of the U.S. DTV transition, the conundrum of the laggard category stalling the transition to all-digital television was ultimately solved by government intervention, motivated mainly by the twin desires of providing more spectrum for mobile broadband service and the lure of large sums of money to come from auctioning the broadcast spectrum: phased-in requirements for DTV broadcasts by all broadcasters, phased-in requirements for DTV reception capability in all receivers, labeling and signage requirements for products at retail establishments, cable carriage requirements, on-air notice requirements, a date certain for analog TV shut-off and a discount coupon program run by the federal government to offset the cost of digital-to-analog converter boxes for consumers.

While Next Gen TV also has a few regulatory requirements, aimed mostly at protecting consumers, it is primarily envisioned as an all-voluntary industry-led transition. Will a voluntary conceptual framework allow the Next Gen TV transition to reach critical mass and then get past the laggard stage of consumer adoption and proceed to an era of maximized Next Gen TV-only broadcasting? Or will government intervention eventually be necessary in order for broadcasters to get access to the entirety of the VHF/UHF broadcast channel assignments for deployment of Next Gen TV service while avoiding disenfranchising a significant number of laggard consumers? Time will tell, but now is definitely time to start pushing up the S-curve!