November has been an exciting time in ATSC 3.0 World. A confluence of important public announcements and major industry milestones echoed the growing momentum of broadcasters looking toward the next generation television platform as the next logical step in the evolution of broadcast media. Below is a top-level survey of recent activity in progress toward bringing next generation television broadcasting to the marketplace.

On November 7, NAB and the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) issued a press release announcing our cooperative effort in Cleveland, Ohio at Tribune station WJW to operate a fully functioning ATSC 3.0 test station. The test station has several overall purposes:

- Serve as a neutral test facility for broadcasters, consumer electronics and professional equipment manufacturers to test prototype and early commercial equipment and services and explore equipment interoperability;

- Operate as a “living laboratory” venue for various testing and “plug fest” activities centered on ATSC 3.0.

Some equipment racks at the NAB/CTA ATSC 3.0 Test Station hosted at Tribune station WJW in Cleveland

The test station operates on UHF channel 31, which was WJW’s pre-transition DTV channel. When WJW returned to channel 8 (their NTSC analog channel) as a permanent home for their digital operations in June 2009, the channel 31 RF system was left in place and channel 31’s service area was preserved in the DTV channel assignment scheme, making it an excellent foundation for rapidly assembling an ATSC 3.0 station. More than a dozen companies have contributed equipment to this all-industry project so far and interest continues to grow. Over the coming months, the Cleveland facility will be a focal point for proving out the end-to-end capabilities of the full ATSC 3.0 set of standards.

On November 15, Pearl TV issued a press release announcing their intention to use Phoenix, Arizona as a “model market” for ATSC 3.0 service. Ten TV stations in the Phoenix market will participate in deploying the model market.

Broadcast antennas at South Mountain Park in Phoenix AZ

The Phoenix model market project will be a comprehensive effort to show how next-generation ATSC 3.0 technology can be deployed while maintaining existing digital TV service for viewers. Stations owned by E.W. Scripps Company, Fox Television Stations, Meredith Local Media Group, Nexstar Media Group, TEGNA, Telemundo Station Group and Univision Communications will participate in the project. Coordinated by Pearl TV, creating an end-to-end model system will help foster industry consensus and drive ecosystem development.

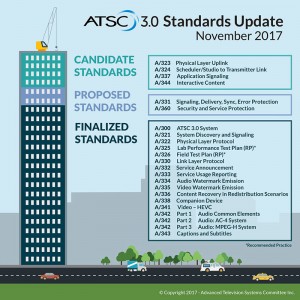

Current version of the ATSC 3.0 Standard “Building”

In the month of November, ATSC completed 9 ballots on various levels of technical standards or amendments to standards pertaining to ATSC 3.0, with an additional 12 ballots that will be completed by the end of December. That’s a lot of paper (or Megabytes of digital ink and paper) and quite a pace for the latter stages of the ATSC 3.0 standards program, which encompasses a total of 21 separate basic standards along with a growing number of amendments.

Of course, completing the initial 3.0 standards will not be the end of the work for the technical standards body; there are a number of Amendments anticipated for additional functionality, Recommended Practices to help ease implementation, and then everything else new (thanks, bootstrap signal!) that becomes ATSC 3.1, 3.2, and so forth, and eventually any arbitrary X.Y version beyond that (where X and Y are integers and X≥4 and Y ≥0) .

Perhaps most significant among November achievements was the adoption of the FCC Report and Order on next generation television at the November 16 Open Commission Meeting. Here’s a quick historical timeline leading up to the November 16 vote:

The original Petition for Rule Making from NAB, CTA, APTS and AWARN asking that the FCC authorize next generation television broadcasting was submitted to the FCC in April 2016. The FCC gathered public comments and subsequently issued a Notice of Proposed Rule Making on Next Gen TV in February 2017 (docket 16-142). Comments and Reply Comments were filed in May and June and the Report and Order (R&O) and Further Notice of Proposed Rule Making (FNPRM) was then voted and adopted on November 16. The text of the full Report and Order was released on November 20. Start to finish in 19 months.

Waiting for the November 16 FCC meeting to begin

Contrast that to the Digital TV process: the original petition for advanced television services (digital wasn’t a thing yet) was submitted to the FCC by 58 broadcast organizations in February 1987 and the FCC issued its first Notice of Inquiry in July 1987, along with the formation of the public/private FCC Advisory Committee on Advanced Television Service in September 1987. This marked the beginning of a long nine-year analytical, test and evaluation period finally resulting in adoption of the ATSC DTV technical standard (well, except for the video formats portion of the standard) as the basis for digital television broadcasting in December 1996. How times change!

Obviously there are lots of details included in the 120-page R&O but perhaps the most radical aspect of the document isn’t what is there but what isn’t. And what isn’t there are a lot of the kind of strict technical requirements and forced time schedules that typified the DTV transition. For DTV, in the struggle between the dichotomy of service certainty through regulation and innovation through marketplace flexibility, certainty won out in the regulatory process. For that time period, it was no doubt the right decision—broadcasters made signals available according to a government schedule, manufacturers made products according to a government schedule, the government prescribed RF channels for DTV, the government’s DTV converter box coupon program protected the low income portion of the public, and today analog broadcasting is all but a distant memory. It’s a success story, but a success story from an older (simpler?) era in media regulation.

It’s a different competitive media landscape now. While government regulation of media still has an important role in interference prevention, life safety issues and a few other areas, policies aimed at choosing technological winners and losers or forcing adoption of technologies along a prescribed time scale just don’t make a lot of sense for a broadcast industry that wants to keep competitive pace with the rest of the unregulated media and their blistering pace of introduction of new services. By not requiring more than the physical layer portion of the ATSC 3.0 set of standards for free television service (e.g., ATSC A/321 and A/322 with a five-year sunset), and allowing broadcasters and manufacturers to proceed to implement next gen TV at their own pace, the FCC has made a huge change in the way that broadcasting has been regulated. The age of permissionless innovation has arrived for broadcasting!

I first heard the phrase “permissionless innovation” in the context of a regulatory approach for next generation TV at a speech by FCC Commissioner Michael O’Rielly at the ATSC Broadcast Conference in May 2016, and then later at a talk he gave for the Association of Federal Communications Consulting Engineers. It’s a great phrase, typically used to characterize how new Internet technologies and services appear and have been able to evolve without regulatory strictures. I became enamored with it. While its origin might be a little foggy, it is most aptly explored in a 2014 (2nd edition in 2016) book by Adam Thierer titled “Permissionless Innovation: The Continuing Case for Technological Freedom. Thierer paints the general regulatory landscape for new technologies as a tension between “permissionless innovation” and the “precautionary principle” which is a not-too-far-off characterization of the current and former treatment of broadcasting.

Thierer says that permissionless innovation “refers to the notion that experimentation with new technologies and business models should generally be permitted by default. Unless a compelling case can be made that a new invention will bring serious harm to society, innovation should be allowed to continue unabated and problems, if any develop, can be addressed later.” On the other hand, the precautionary principle “refers to the belief that new innovations should be curtailed or disallowed until their developers can prove that they will not cause any harm to individuals, groups, specific entities, cultural norms, or various existing laws, norms or traditions.”

Authorizing next gen TV was not without controversy among the five FCC Commissioners, and the 3-2 vote in favor of adoption was split between the Republican “ayes” and Democratic “nays,” with positions generally occupying the opposite ends of the continuum between permissionless innovation and the precautionary principle. You can watch the presentation of the item and all the discourse from the Commissioners online here. The ATSC 3.0 agenda item begins at the 195 minutes and 47 seconds timestamp (yes, it was a long meeting). It’s not only great theater to watch but also somewhat satisfying to see the high degree of passionate rhetoric and staunch defense of strongly held views, whether you agree with them or not. And since you know how it all ends, it’s no spoiler alert to say the good guys (meaning broadcasters, manufacturers and eventually consumers) won!